Beyond the Ides of March: Insight from Shakespeare

March 13, 2025

- Contact

- Lisa Patterson

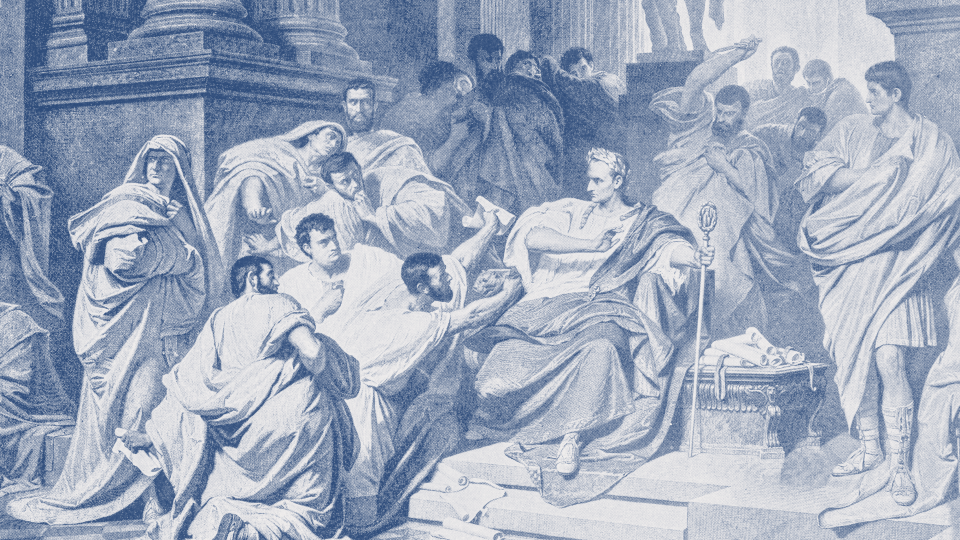

March 15 earned notoriety in 44 BCE with the assassination of Gaius Julius Caesar. Known in antiquity as the Ides of March, the day initially marked the first full moon of a new year. Now, in part thanks to playwright William Shakespeare, the day lives in infamy.

With a little help from Charles A. Dana Professor of English Emerita and Shakespeare scholar Cynthia Lewis, we can learn what Shakespeare had to say about foresight, belief and human nature.

Prophets in literature have a tendency not to be believed, and the Soothsayer in Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, who repeatedly warns Caesar "Beware the ides of March," is one such failed prognosticator.

Perhaps he would more easily convince Caesar not to venture to the Capitol, where the leader will be assassinated by the likes of Casca and Brutus, if he were more specific.

"Beware your friends' brutality on the ides of March," for example, "especially the one with the lean and hungry look."

But the nature of prophecy in Shakespeare's plays, as in other writers' hands, is one of mystery and vagueness. It requires astute interpretation on the part of the listener, who is often disinclined to pay enough attention or ill equipped to figure out the prophet's meaning. Caesar rather arrogantly sees himself as invincible.

In Antony and Cleopatra, another play about an ill-fated Roman, the women in Cleopatra's court miss the implication of the Soothsayer's statement that one of them "shall outlive the lady whom you serve."

"O excellent," one of Cleopatra's women responds, "I love long life better than figs." Her enthusiasm turns out to be ironic when she dies of a snake bite just moments after her mistress, Cleopatra, herself collapses from the asp's poison.

Antony, however, is more adept at fathoming the words of the Soothsayer, who says of himself, "In nature's infinite book of secrecy / A little I can read."

When he warns Antony to steer clear of Octavius Caesar (Julius's nephew), Antony sees why he should. "The very dice obey him," says Antony of his nemesis. Even so, Antony ignores his own good sense, reflected in the Soothsayer's prophecy, arrogantly wages war on Caesar, and tragically loses.

In their haste to prove their manhood, Romans incline to believe what they want to believe.

On at least one occasion in Shakespeare, in a late play called Cymbeline, a Soothsayer interprets a prophecy sent to earth by the gods. He gets to cheat, since the meaning of the prophecy has already been made clear by the unfolding of the play's events. No matter, though. At the conclusion of a play with an extremely complicated plot–one whose final scene is calculated to comprise 24 separate dénouements (plot revelations)–the characters and the audience alike are so relieved to have squeaked by with a happy ending that they hardly notice what the Soothsayer knows or care how he knows it.

On the ides of March in 2025, we may find ourselves wondering whether we are any more skilled at foresight than Julius Caesar or Marc Antony. In fact, the last year, one of unpredictable political twists and turns, may seem as baffling in retrospect as it was indiscernible when it was still the future.