Davidson Faculty Team Up to Explore the Benefits and Pitfalls of AI

November 15, 2024

- Author

- Mark Johnson

Gayle Kaufman is a Davidson College professor, researcher and author – and appreciated the pit crew.

Kaufman joined an 8 a.m. session – even professors sometimes take early classes – for coaching on “Claude,” an Artificial Intelligence assistant developed by Anthropic. Kaufman had the counsel of two of the college’s technology staffers and Laurie Heyer, math professor and associate dean for data and computing.

Kaufman asked how much text could be uploaded into Claude’s query box.

“They were able to put a whole Harry Potter book into it,” said Andrew Denny, AI Innovation Fellow with the college’s library.

Kaufman tested Claude with three pages from a 23-page interview about LGBTQ marriages, asking for the main themes. Claude quickly spit out a bulleted list – a time-saving overview. Kaufman suggested doing the same across multiple documents, which would help spot trends. Because this experiment used Claude within the Davidson-only interface, the data does not get used for other training – “a little walled garden,” said Brooklyn Madding, communications, technology and outreach coordinator for the college’s Technology & Innovation division, who helped lead the session.

Artificial Intelligence generated both inestimable possibilities and a truckload of anxiety as it grew quickly and widely available over the past year. A core group of Davidson faculty and staff, supported by the president’s office’s investment in professional-level AI tools, are tackling both the opportunities and angst. They created and are leading the AI Innovation Project to learn how AI works, guard against its misuse and figure out how it can help their teaching and research, from computer science to music. The effort grew out of the college’s strategic planning with the hopes that what the group learns will help the college understand and harness AI. The project exemplifies the liberal arts ethos of constantly learning and striving to expand knowledge.

“There’s a spirit of innovation, of experimentation and of skepticism,” Heyer said. “We saw this tsunami and said, ‘We need to get ahead of this. We need to have knowledge across the faculty about these tools and, then, prepare our students for a world in which these technologies are pervasive.’”

The college paid to license, and make available to faculty, professional versions of: OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Microsoft’s Copilot, Anthropic’s Claude and, for the library, Elicit, developed by Ought.

The project’s leaders are creating mentored, communal-learning sessions, such as the one Kaufman joined. They also have held larger presentations on what AI is, its drawbacks and guides for harnessing its power accurately and effectively. Smaller sessions over the semester include: creating a customized ChatGPT, using AI to analyze images, and drawing ideas or cautions from the book “Teaching with AI.”

Heyer encouraged these “learning communities” at an introductory session in August, saying: “We’re going to need each other.”

In that session, Matt Jackson, application analyst with the Technology & Innovation division, defined AI as a computer making decisions or completing tasks typically done by humans. He highlighted, as an example, large language models, a set of technologies that consume massive volumes of words and phrases and predict the relationships between them – training to answer questions. He offered a quick guide for making inquiries to AI, including:

- Ask AI for help rather than to produce a finished product, such as editing rather than writing.

- Identify key contexts.

- Make adjustments as you go – iterate.

- Don’t use jargon.

- Critically read the results AI offers.

- Adapt. Technology changes rapidly, and so should our approach to using it.

Faculty and staff in the project have zeroed in on the mix of risk and advantage that AI presents. One professor described it as “incredibly bad at math,” unable, for example, to correctly count the number of days between two calendar dates, but he praised how helpful the technology is in revising letters.

Susana Wadgymar, assistant professor of biology, has secured professional level ChatGPT access for her class on biostatistics, a course in which students look at how experiments are designed, and how to examine and analyze biological data. She also designed a customized ChatGPT for the class to use on specific assignments.

If students engage with ChatGPT on an assignment, they have to include a statement on how they used it. If they use the customized version, they have to include a transcript.

“I told my students,” Wadgymar said, “that we are experimenting together.”

She described AI as an easy way to gather generalized information but short on providing deep learning. Students’ use of the tools will help them recognize bad output, Wadgymar said, and students will be able to identify what sets them and their work apart from something an AI tool can provide: “What makes the human experience needed?”

Philosophy Professor Paul Studtmann incorporated ChatGPT into a class with a sense of both encouragement and trepidation. Students wrote an essay and, then, spent a class using the AI tool to edit. They highlighted any changes and wrote a paragraph on whether they were improvements or mechanical adjustments.

“ChatGPT is very limited in its ability to develop original ideas,” Studtmann said, “and yet has a remarkable ability to take a piece of writing and improve it significantly. All the students noted this in their paragraphs. And there is a risk that, in the process, the author’s voice is lost. Several of the students noticed this as well. With that said, all the students concluded that ChatGPT can be a very useful tool.”

Mark Sample, chair and professor of film, media, and digital studies, helps lead some of the AI discussion sessions and said the project is reinforcing for many of the participating faculty the importance of liberal arts pillars, such as engaging with ideas at a deep level and backing up arguments with research.

Professor of English Suzanne Churchill deployed AI in several classes, including a first-year writing class that investigated how AI may affect writing. Students tried a series of small experiments, such as requesting an essay on a topic or uploading a poem and asking for an analysis. Churchill said the results were well written, sounded authoritative and improved with each query, but they did not make substantive points. Students, though, still benefited.

“It helped them see the kind of fluff that we want to get out of our writing,” Churchill said. “It can help with specific tasks, but it can’t grapple with the thoughts and ideas.”

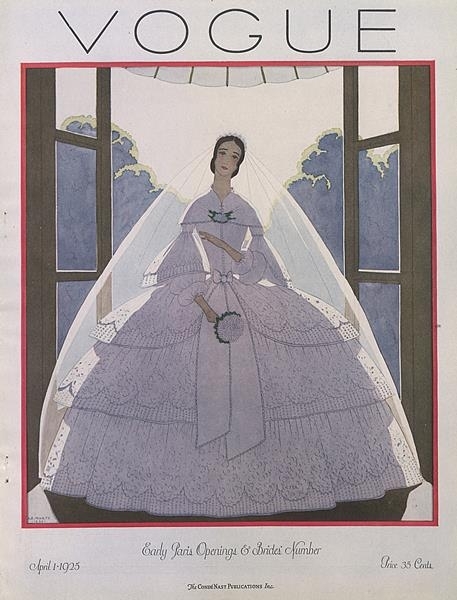

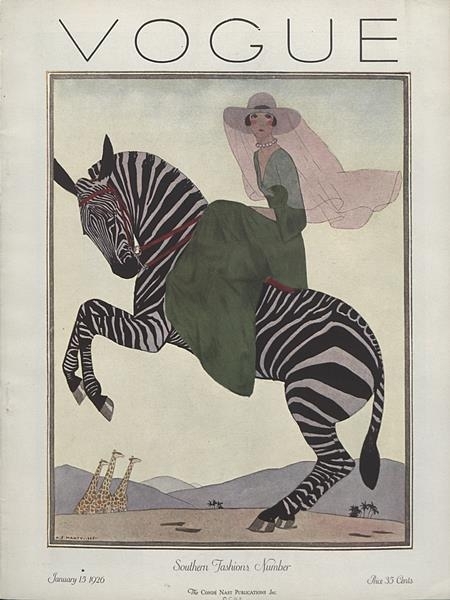

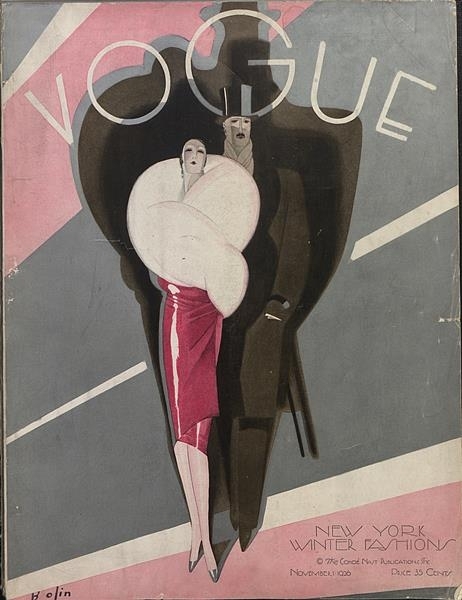

Lexi Fletcher ’25, a data science major in another of Churchill’s class, asked ChatGPT to analyze a set of Vogue magazine covers from the 1920s, the decade of women’s suffrage and flappers. The AI program tended to offer obvious or nonargumentative observations, such as highlighting the art deco style. When it was fed more context about history and society, the results got more complex.

“As people, we can’t escape feelings or context, but AI can,” Fletcher said. “Is that good or bad? What we wanted was a bigger conversation, and it couldn’t produce that.”

The project group is learning, among other gains, that AI cannot substitute for their work, but it can help speed them up.

Shelley Rigger, vice president for academic affairs and dean of faculty, said the professors’ role is to teach students to be better than AI – to add value to what the AI programs can do.

“They will use AI in their careers, but they need to be able to do more than the AI can do,” she said. “They need to be able to critique the output and to supplement the computerized results with the kind of thinking and judgment that humans do best. What we’ve learned so far from the AI Initiative is that these technological tools are far from perfect – there is plenty of room for Davidson students and graduates to use their own minds, knowledge and creativity to be better than the machine.”