Bigger Picture: From Battlefield to Village, Ross Boyce ’01 Wages War on Malaria

August 5, 2019

The possibilities of medicine and the destructiveness of war somehow meshed over nearly two decades to the day last fall when Ross Boyce got $1 million to save lives.

The National Institutes of Health bankrolled his project aimed at reducing malaria and the number of its victims in western Uganda.

“We were legit,” he says.

Pieces of Boyce’s life—confronting death, an eagerness to solve problems —stacked up to create that moment like the accumulated components and ideas that give birth to an invention. There were the chemistry classes at Davidson, ambush positions in Iraq, labs at the University of North Carolina, a return

to the battlefield instead of med school, the stacks of dusty records in a dark Uganda clinic and the sweaty, sandy hikes to East African mountain villages.

“I need to do something else.”

Blame imperfect vision.

Boyce’s high school graduating class in Clemmons, North Carolina, totaled about 55 students. He spent a childhood around airplanes and the military thanks to his father, a pilot, and uncle, who were both U.S. Air Force Academy graduates. Colorado Springs intrigued him, but his vision fell short of 20/20. He couldn’t be a pilot. In his view, there wasn’t much to do in the Air Force other than fly, so he signed up for the Army.

Two high school summer soccer camps at Davidson had put the school on his college list. He chose to become a Wildcat and emerged as a chemistry major and ROTC cadet aiming for med school and a military doctor’s life. He was a meticulous student but also mischievous enough to start a contest with his roommate and co-chemistry major, Kurt Hirsekorn, trying to bounce a superball from the third floor stairwell in the Martin Building to the basement and back.

Chemistry Professor Erland Stevens, who confessed to joining the superball escapade, remembers that while most students were content with standard composition notebooks, Boyce would pick out a sturdy, hardbound version. He carefully and continually worked on rebuilding a 1946 Willys Jeep back home.

By senior year, med school looked like more years in classrooms and labs. He may not have recognized it then, but he didn’t like spending a lot of time on the philosophy and theory behind an endeavor without moving it forward. He was restless. Going out and doing something grew more appealing.

Boyce switched from future Army doc to the infantry.

He graduated from Davidson in May 2001, commissioned as a second lieutenant. Four months later, hijacked airliners plowed into the World Trade Center, Pentagon and a Pennsylvania field. By 2004 he was leading a reconnaissance platoon in Iraq. What mattered most were the 30 soldiers under his command—getting them back home.

“Duty, loyalty, responsibility to the people who you are tasked with being in charge of,” Boyce says. “It’s a powerful force capable of pushing you to do things you didn’t think you are capable of doing.”

They raided some houses and occupied others for reconnaissance positions. During his year there, he saw Iraqis killing each other in the street.

“I left thinking that I need to do something else with my life,” he says.

However chaotic the environment, he, more than many, had engaged with the community— in the towns, in those houses, understanding the toll of war and the needs.

Everyone Else Was Going Back

His Army service complete, Boyce headed to medical school at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. It was comforting to return to a classroom. No one was shooting at him.

“Year two of med school was the surge [of troops in Iraq],” he says. “More people were going back— people who I knew. Well into my second year, it’s hard to be here in school when people I know, am friends with, are going back. This was when every night on the news they would run the list of people killed. There were a few names I knew.”

He told his family that he had been called up from the “ready reserve,” that he HAD to go. The truth was that he volunteered and knew they wouldn’t understand. Even then, they asked why he wouldn’t seek a medical school deferment, betraying the flaw in his cover story.

The Army’s sometimes head-scratching protocols sent Boyce, an experienced combat veteran, for retraining by instructors who had yet to see combat. He ended up assigned to a North Carolina National Guard unit whose initial mission was outreach to Iraqi Army units. The Iraqis ultimately declined the partnership.

The National Guard unit’s mission evolved, and Boyce settled into a role as an operations officer, confident in his skills as a planner. He planned the first helicopter-borne assault the N.C. Guard units had ever executed. He started getting more attention from senior officers who placed him in charge of the civil affairs unit.

He spent every possible day talking with local Iraqis, with farmers. How are your crops doing? How are you getting them to market? He and his soldiers fixed roads, put in irrigation systems, vaccinated farm animals, trained midwives and built agricultural coop buildings. He once googled, “How do you build the foundation for a building?”

Boyce confronted problems that needed to be fixed, and he had to figure out the solution in a land of challenging supply chains and powdery sand that infiltrates everything. He liked the work. He still aimed to complete medical school, but his interest in population health and public health challenges spiked on his return to the Biblical lands of the Tigris and Euphrates.

“If you treat a patient for cholera [a severe dehydration disease spread in unsafe water], you treat one person,” he says. “If you give a village clean water, 10,000 people get clean water.”

The Untrodden Path

Boyce’s second tour in Iraq brought some balance to the first— and a third Bronze Star medal. One of the first two included recognition for heroism in combat.

“When I left Iraq the first time, I felt like I was leaving a house on fire,” he says. “When I left the second time, I felt like even if the house was on fire, I had done my best to put it out.”

Years later, he spoke at Davidson about his military experience with the same honesty, and took heat from some in the audience who saw him as the face of a U.S.-led, and improvidently begun, war, Stevens says.

“His message seemed to be, ‘Here’s what it means to be a soldier,’” Stevens says. “He wasn’t defending it, and he wasn’t apologizing for it. It was apolitical. It changed my perception of what people in the military go through.”

Boyce returned to med school, but left again for a master’s in public health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Med school, it seemed, would get done on an installment plan. After his final year, he landed an internal medicine residency at Massachusetts General Hospital—the glitz of Harvard.

Mass General operated a partnership around HIV research in Uganda, where the hospital’s residents could spend several weeks. Boyce went thinking he would never return to Uganda, that it was a step away from conflict medicine, doctoring in crisis zones, such as Doctors Without Borders. Then he sampled that experience in Somalia, where he essentially couldn’t travel anywhere without a military convoy.

“I couldn’t leave the hotel,” he says. “It was like living in the Green Zone in Baghdad. How much impact can you have?”

He also had not completely left Uganda behind. He saw hundreds of children with malaria, a disease for which there were ample preventions and treatments.

“It clicked. It’s not just the disease, it’s the geography,” Boyce says. “How do you get the people down off the mountain [to the clinic]? It was the problem-solving piece, like in Iraq: Get the medicine to the people or the people to the medicine.”

He wanted to tackle malaria. The traditional path in medicine is an apprentice role in research: Work with a mentor, achieve small victories and small grants that, step by step, build up to recognized work and large grants. Successful researchers ultimately fund themselves. Two problems: Nobody was already doing what Boyce wanted to do. Second, he wanted to move the research halfway around the globe and act on it right there. Research to him was a mechanism through which he used his skill set.

Going around the established career ladder in any field of work requires fortitude, Stevens says, but particularly in a profession that values proving yourself.

“Being able to say, ‘I could do that, but I want to do something else,’ takes a confidence and boldness,” Stevens says. “A confidence to reject what your profession holds in highest regard.”

Boyce found that alternative route at a familiar place. UNC had established a fellowship in infectious disease that offered mentors, collaborators, a recognized research group on tropical diseases, particularly malaria, and the support to hit the road when needed. He landed the job and the excursions to Uganda continued.

Harry Potter

The clinic that served as a base is in Bugoye, a village in far western Uganda, near the border with the Democratic Republic of Congo, or, as Boyce says, the end of the road. He spent the first trips trying to understand the basics. How many cases of malaria are there? He would go into a dark room at the clinic and page through old notebooks containing penciled numbers, likening the scene to Harry Potter lifting up dusty spell books in a hidden chamber.

Boyce was counting the malaria cases, jotting data onto paper, looking at five or six years of numbers. He was charging at a centuries-old disease with no money and insufficient information.

Raquel Reyes, a Harvard Medical School graduate and assistant professor of medicine at UNC, met him on one of his residency trips to Uganda. She saw immediately that he brought a different approach to the experience. His outlook and interactions with people impressed her.

“He walked the land out into the villages and mapped the villages out, assembling data points and meeting people,” she says. “He had a larger picture than most people who go.”

He earned the trust of local Ugandans, she says. Video of a November visit shows him meeting with a local mayor, medical staff, educators and others who call him, “Dr. Ross.”

“You can tell when someone is real and committed,” Reyes says. “And going to stick.”

When the two got engaged, residents of the village presented them with traditional wedding clothes and held a ceremony.

The early months of his UNC project in Uganda turned into something of a gritty, boots-on-the-ground parallel to the step-by-step research track from which he had diverted. Boyce turned his cobbled-together data into a small grant that enabled him to build a map of the disease in the region. He got money for a GPS system to improve his map and identify where the malaria cases were coming from—some villages more than others.

“I would go out,” he says, “and say, ‘Show me where your village begins and ends.’”

He produced a paper or two about geographic differences and leveraged that into $25,000 for further work, including money to install solar power at the clinic, some computers, lights and refrigeration so they could keep samples.

“He’s been able to find small research pots of money,” says Jonathan Juliano, M.D., associate program director of UNC’s Infectious Disease Fellowship Training Program. “And do good research regarding the diseases in his community, while at the same time developing resources in the community for taking care of his patients.”

Then a $50, 000 grant came through, followed by $100,000 from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation last fall. Just weeks later, the $1 million was announced by NIH, an organization that typically focuses more on how diseases work and how to combat them than the work in a particular community.

Along the way, he made repeated treks into the mountains where workers in the region hiked down with bags of harvested coffee beans. He made multiple trips to debunk the myth of a hydroelectric dam, supposedly built in the 1950s or 1960s, that some Ugandans blamed for malaria. Instead he found only a mining pond at such a high altitude that mosquitos would never nest there.

Coffee Beans and Cell Phones

Boyce’s most recent study expanded to three clinics across southern Uganda and is looking to go further. On his visit last fall, his Ugandan partners conducted focus groups with local women to help determine if treating their infant carrier wraps with insecticide would reduce mosquito bites and malaria in the children.

He also met with representatives from an international coffee company. Most coffee produced in Uganda is the more mundane robusto variety, but western Uganda is a rare site for Arabica coffee bean crops. The coffee company wants healthy workers so that they can bring in the crops, but they don’t know how to provide health care. One possible step is that the coffee company would provide cell phones to growers.

That helps the company, as its representatives can text when they needed the beans brought down from the mountain or to say that it’s time to plant fertilizer. Those same phones could be used to text the clinic when there was an emergency or to report a spike in malaria cases.

Boyce sees the progress in the evolution of his own role. During his November trip, he was meeting with local leaders, medical teams and potential funders. The dusty books, the hikes and the maps were behind him.

He feels a responsibility to his Ugandan community, like the duty to his soldiers in Iraq—that powerful force that pushes a person beyond what they thought possible. The recent grants buoyed both his efforts and outlook, but uncertainty looms. The grants fund a defined purpose for a limited time.

“We ask a question. We answer it,” Boyce says. “If the answer is ‘Yes, this works,’ how do we keep it going?”

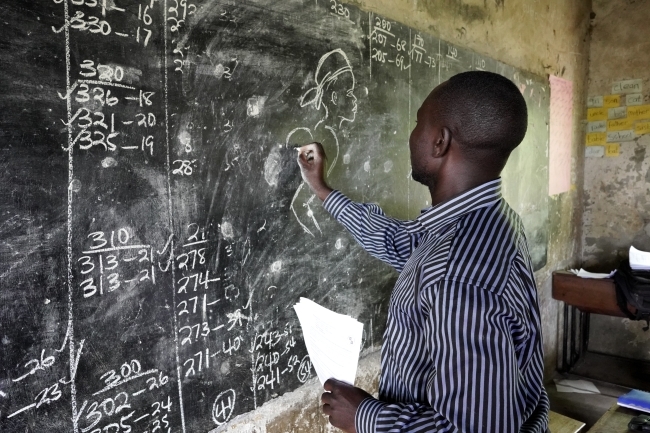

Ross Boyce '01 walks the villages and mountains of Uganda, meeting people, mapping the region and assembling data. His approach has paid off -- with awards from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the National Institutes of Health, Boyce and his Ugandan partners have made strides against malaria. His most recent study expanded to three clinics across southern Uganda.

If you would like to learn more about Ross Boyce’s work in Uganda, please contact him at ross_boyce@med.unc.edu.