Art and Science Comingle to Create Healing Exhibit Now on Display

September 27, 2022

- Author

- Chris Alexander

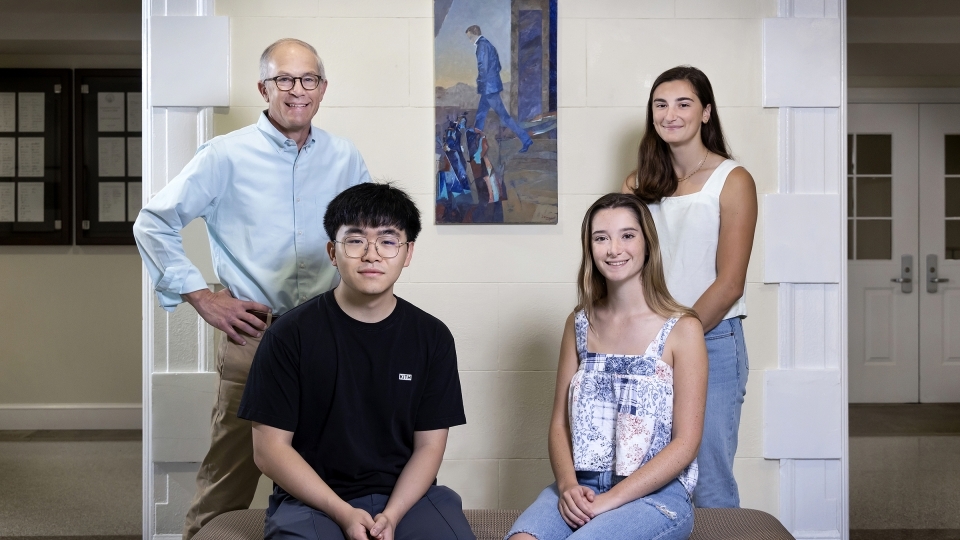

Biology Professor Dave Wessner with students David Peng '22 and Cathleen Krabak '23 (seated) and Nella Tsudis '23, surrounding “El Extranjero” by artist Delia Cugat.

The 12 students in Dave Wessner’s course on the biology of COVID-19 knew they would spend hours poring over scientific articles—but studying an etching by Edward Hopper, a painting by Delia Cugat or a screen print by Nicholas Monro?

In fact, that’s exactly how the lucky dozen spent much of the spring 2022 semester.

Working in pairs, Wessner’s students selected images from Davidson’s Van Every/Smith Galleries that reflect the pandemic’s impact on them, their families, friends and communities. Each pair wrote a curator’s statement for their piece and a longer essay about the scientific or health policy issue the artwork highlights.

“Using Art to Learn More About COVID-19,” a collection of these images and reflections, is on exhibit through the end of September in the Chambers Building lobby.

Art and the Lived Experience of Disease

A respected virologist, Wessner wants his students to understand the science behind the origin, spread and evolution of viruses. But he also wants them to understand the lived experience of disease.

This commitment stems from his own experience.

In 1996, Wessner was conducting research on coronaviruses as a post-doctoral fellow at the National Navy Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland. Twenty miles away, the AIDS quilt spread across the National Mall. Each square told the story of a person who had died from HIV/AIDS.

“I read stories in these panels about people who were disowned by their families, who lost their jobs, who were kicked out of their apartments and died homeless,” he said. “I realized that we can’t just study science for science’s sake. Diseases show us how science affects society, real people.”

Wessner decided then to teach students about infectious diseases in a way that explores how disease affects whole persons and communities. He credits Lia Newman, director and curator of Davidson’s Van Every/Smith Galleries, with the suggestion to make art a part of his teaching.

Newman advocates for Davidson’s art collection to support teaching practices across the curriculum.

“Some people don’t have much exposure to art, or they think they lack the vocabulary to talk about art,” said Newman. “I want people to feel comfortable looking. People can use languages they already know from other disciplines to begin to ‘read’ a work of art just as they would read a text in a literature class.”

Wessner first incorporated art into his course on the biology of HIV. That experience inspired him to develop a more robust art assignment for his course on COVID-19.

“Just Look”

In early March, Wessner’s students met with Marisa Pascucci, gallery and collection coordinator for the Van Every/Smith Galleries. Davidson’s collection currently contains about 4,000 pieces. Pascucci pulled a few works she thought might resonate with the students.

“Just look,” she told them. “What do you see? There are no right or wrong answers. What’s happening in this piece? What do you see that supports your reading of it?”

Wessner asked his students to use these questions to address two others: How can art convey information about COVID-19 to a general audience? How can we interpret works of art within the broader context of public health?

Then, said Hannah Gould ’22, “they let us loose in the basement with piles and piles of art.”

The images include a range of styles and content. But the students’ reflections reveal consistent themes.

Reacting to Grignan, Todd Webb’s black and white photo of a simple stone staircase in Provence, Era Mero ’22 and Anna Montgomery ’22 wrote that the piece evokes “a sense of loneliness and isolation much like what people felt during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Mary Kaufmann ’22 and Kiki Fagan ’22 chose Night Shadows, an etching by Edward Hopper. A figure walking at night suggests loneliness, psychological distress and uncertainty about what lies ahead.

David Peng ’23 and Cathleen Krabak ’23 saw “the trepidation of a foreigner entering a new land” in Delia Cugat’s El Etranjero. A man stepping into a fragmented landscape symbolizes how “the entirety of the world was thrust into the unknown when the COVID-19 pandemic struck.”

Some found the preparation of the exhibit unsettling. As Nella Tsudis ’23 noted, “there were no degrees of separation between us and the pandemic we were studying.”

Talking and writing about these pieces meant facing the anxieties and losses the students experienced over the past two and a half years. Loneliness and fear of the unknown dominate their reflections.

A Healing Space

“If you could say it in words, there would be no reason to paint.”

Kaufmann and Fagan included this remark by Edward Hopper in their reflection on Night Shadows. It underscores the power of art to help individuals process feelings.

This was true for Tsudis.

“Everyone interprets the art differently because of our own experiences,” she said. “That’s what makes art powerful. Public health officials should use art to convey important messages to broad audiences.”

Gould said the experience was especially meaningful for seniors.

“At the end of college, it allowed us to look back at what has happened,” she said, “and forward to how we can prepare for the next disease.”

While engaging with art can be therapeutic for individuals, Kristi Multhaup, Vail Professor of Psychology, emphasizes the role art plays in forging collective identities and communal healing: simply, art brings communities together.

As examples, she cites murals on the walls of Belfast, Ireland, sketches by concentration camp residents, the Black Lives Matter mural on Davidson’s campus, and the AIDS quilt that had such a powerful impact on Dave Wessner.

Wessner is pleased the exhibit means so much to his students. He hopes it becomes a source of healing for the whole community.

“We’ve all been traumatized by COVID-19,” he said. “Lots of people are just now processing this trauma.”